When Hating Your Landlord is an Act of Piety

What is a Peasant? Pt. 2

If you missed Part One of this series, read it here.

The first time I learned about the F-word, it was illustrated as a pyramid. On top sat the king in majesty, followed below by the nobility flaunting silk chaperons, then knights wearing armor from a hodgepodge of eras, and finally, wallowing at the bottom, the great and pitiful agrarian masses. I called it “feudalism,” not knowing that See Inside the Middle Ages: An Usborne Illustrated Book had just taught me an academic profanity regarded by many medievalists as lazy, reductionist, and a tool of self-aggrandizing Whig historians.

Indeed, agrarian workers in this time period, or what we generally refer to as “peasants”, lived under many different customary, legal, and cultural realities (as discussed in Part One), not just one big feudal umbrella. But their relationship with production, their means of sustenance, and their fundamental place in society — the necessary muck that by mere contrast exalts the honorable few — remains globally recognizable in spirit, if not necessarily in structure.

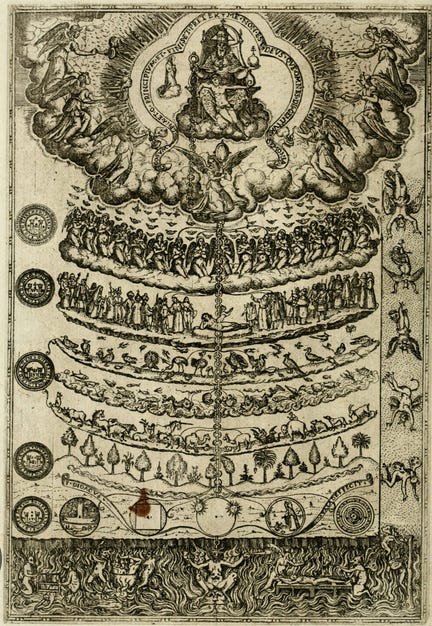

It is an existence that can only be maintained if the peasant consents. Consent was traditionally wrung from them and maintained by law and violence. Over time, most peasants seemed to accept that their place in the hierarchy was not only legal and economic, but also fixed as a permanent link in a great cosmic chain: set above animals, plants, and rocks, but trapped below everyone else. To submit to the natural order was an act of virtue that offered salvation beyond dignity on earth. The real danger to the system, then, was not simply about hunger and taxes. It was also the moment when the peasant saw not a master to be obeyed, but a corrupt usurper to be punished.

These moments rarely emerged from a sudden epiphany about the future, but from a furious reaction to a lord or sovereign who had broken their covenant. In the Persianate tradition, this covenant nominally took form as the Circle of Justice, a vision in which the world was a garden and the state was its wall*, ordained by Holy Law to shelter the people with justice, and yet also dependent on their prosperity to remain standing.

In 1850, this theory was put through a violent test. When landlords in Ottoman Bulgaria defied new laws and continued to force them into unpaid labor, 10,000 peasants sent a delegation to petition the sultan for redress before promptly attacking their oppressors. In their eyes, the landlords had become noxious weeds, intercepting tax that belonged to the state and blocking the justice that flowed to them through the sultan from God. To submit to those usurpers was to be complicit in starving both themselves and the state; to root them out was a spiritual obligation.

In this case, the sovereign’s own law, written 11 years before the uprising, gave a proximate justification for the violence. English rebels in the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt operated under a more sentimental logic. When they rose against the imposition of a new poll tax and other longstanding grievances, their rallying cry was for “The Law of Winchester and No Other,” a reference to a century-old statute that had, in the collective imagination, been mystified as an organizing principle from a golden age.

King Edward I had enacted the Statute of Winchester in 1285, commanding private citizens to form watch patrols and raise the “hue and cry” whenever they saw a crime in progress. To king and parliament, this was a cheap way to outsource law enforcement; to the rebels, it was a lost ideal from when the crown relied on the people’s self-organization rather than taxing them to death, imposing maximum wages on poor laborers, and criminalizing the wearing of decent clothing. These seemingly mundane statutes provided the legal casing for a deeper, spiritual truth, voiced by the priest John Ball: that “all men by nature were created alike,” before they were enslaved by “naughty men.”

When the rebels reached London, they hunted down the king’s most hated officials, dragging them out of their hiding places and sanctuaries to face summary execution. Archbishop Simon Sudbury, the Lord Chancellor, allegedly sustained eight sword blows to the neck before finally losing his head. The rebels did not see their deaths as murder, but as raising the hue and cry against thieves who had stolen from the people. John of Gaunt, the king’s uncle, was away from the capital, so in lieu of cutting off his head, they burned down his riverside palace. Rebels also targeted the city’s population of Flemish weavers, whom they regarded as creatures fattened by royal favor and trade privileges while the English commons were suppressed.

On its face, both the 1850 and 1381 revolts seem reactive: the Bulgarians enforced the sultan's new decree to repair the Circle of Justice, while the English sought to restore the “Law of Winchester” as they remembered it. Violent action was provoked by authorities stepping over the line and violating customary rights both real and imagined. But the specific demands by the English rebels were radical and unprecedented for the time: the abolition of serfdom, the abolition of nobility, the confiscation and redistribution of Church land. In defense of what E.P. Thompson called the “moral economy” of social obligations against the tyranny of “progress,” peasants were willing to become would-be revolutionaries.

Most of the time, however, agrarian fury did not manifest as a revolutionary bid for state power. At its most desperate, it was the disorganized violence of simple wretched hunger where the only objective was to loot a bakery, burn down a manor, or rob their neighbors. Yet often, the crowd operated under a stricter internal logic of social correction. When the French government un-fixed bread prices in 1775, and prices predictably soared, peasants across the country stormed into mills and warehouses, seized the provisions, and sold it for what they regarded as a just price; in some cases, they returned the profit to the fuming merchant.

The uchikowashi of the Tokugawa polity represented this compulsion in a more ritualized form. Whenever a headman or merchant exploited the village by usury or hoarding rice, the aggrieved inhabitants would dismantle his home down to its foundations, hack apart the wooden beams, and destroy or scatter his ill-gotten luxury objects amongst the debris. Ideally, participants would never steal those items, for petty thievery would only tarnish their sacred purpose: to physically remove a tumor from the communal body. As long as the peasants respected that boundary and maintained their act solely as a rite of purification, the government, fearful of another uprising, would typically force the target to provide redress and pardon all uchikowashi participants except for the ringleaders. By the 19th century, this cycle had become a known reality. The leaders went to their deaths with open eyes, trading their lives to restore the moral order of their community.

*From The Sublime Ethics by Kınalızâde Ali, c. 1564:

“The world is a garden, walled in by the state

The state is lordship, preserved by law

Law is administration, governed by the sovereign

The sovereign is a shepherd, supported by the army

The army are soldiers, fed by money

Money is revenue, gathered by the people

The people are servants, protected by justice

Justice is happiness, the well-being of the world.”